Storm Shadow

| Storm Shadow/SCALP EG | |

|---|---|

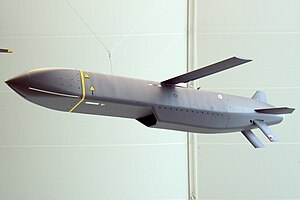

A missile displayed in the RAF Museum, London | |

| Type | Air-launched cruise missile |

| Place of origin | France & the United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 2003–present |

| Used by | See operators |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Matra BAe Dynamics |

| Designed | 1994–2001 |

| Manufacturer | MBDA |

| Unit cost | £2,000,000 (FY2023) (US$2,500,000)[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) |

| Length | 5.1 m (16 ft 9 in) |

| Width | 630 mm (25 in) |

| Height | 480 mm (19 in) |

| Wingspan | 3 m (9 ft 10 in) |

| Warhead | Multistage BROACH penetration warhead |

| Warhead weight | 450 kilograms (990 lb) |

| Engine | Microturbo TRI 60-30 turbojet 5.4 kN (1,200 lbf) |

Operational range | 550 km (300 nmi; 340 mi) |

| Maximum speed | Mach 0.95 (323 m/s; 1,060 ft/s) |

Guidance system | GPS, INS, IIR & TERPROM |

Steering system | 6 tailplanes (4 vertical & 2 horizontal) |

| Transport | Mirage 2000, Rafale, Su-24, Tornado, Typhoon, Gripen |

| References | Janes[2] & The Telegraph[3][4] |

The Storm Shadow is a Franco-British low-observable, long-range air-launched cruise missile developed since 1994 by Matra and British Aerospace, and now manufactured by MBDA.[5] "Storm Shadow" is the weapon's British name; in France it is called SCALP-EG (which stands for "Système de Croisière Autonome à Longue Portée – Emploi Général"; English: "Long Range Autonomous Cruise Missile System – General Purpose"). The missile is based on the French-developed Apache anti-runway cruise missile, but differs in that it carries a unitary warhead instead of cluster munitions.[6]

To meet the requirement issued by the French Ministry of Defence for a more potent cruise missile capable of being launched from surface vessels and submarines, and able to strike strategic and military targets from extended standoff ranges with even greater precision, MBDA France began development of the Missile de Croisière Naval ("Naval Cruise Missile") or MdCN in 2006 to complement the SCALP. The first firing test took place in July 2013 and was successful.[7] The MdCN has been operational on French FREMM frigates since 2017 and also equips France's Barracuda nuclear attack submarines, which entered operational service in 2022.

In 2017, a joint contract to upgrade the respective Storm Shadow/SCALP stockpiles in French and British service was signed. It is expected to sustain the missile until its planned withdrawal from service in 2032.[8][9]

Since 2023, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Storm Shadow missiles have been supplied to Ukraine in large quantities. Multiple Russian ships have been either sunk or heavily damaged by them. [citation needed]

France, the UK, along with Italy are jointly developing the Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon to replace SCALP/Storm Shadow and each nation's respective anti-ship missiles by 2028 and 2034.

Characteristics

[edit]

The missile weighs about 1,300 kilograms (2,900 lb), with a conventional warhead of 450 kilograms (990 lb). It has a maximum body diameter of 48 centimetres (19 in) and a wingspan of three metres (120 in). It is propelled at Mach 0.8 by a Microturbo TRI 60-30 turbojet engine and has a range of approximately 560 km (300 nmi; 350 mi).[10]

The weapon can be launched from a number of different aircraft—the Saab Gripen, Dassault Mirage 2000, Dassault Rafale, the Panavia Tornado, both the Italian Tornado IDS and formerly the British Tornado GR4 (now retired),[11] and a modified Sukhoi Su-24.[12] Storm Shadow was integrated with the Eurofighter Typhoon as part of the Phase 2 Enhancement (P2E) in 2015,[13][14] but will not be fitted to the F-35 Lightning II.[15]

The Storm Shadow's BROACH warhead features an initial penetrating charge to clear soil or enter a bunker, then a variable delay fuze to control detonation of the main warhead. Intended targets are command, control and communications centres; airfields; ports and power stations; ammunition management and storage facilities; surface ships and submarines in port; bridges and other high value strategic targets.

The missile is fire and forget, programmed before launch. Once launched, it cannot be controlled or commanded to self-destroy and its target information cannot be changed. Mission planners program the weapon with details of the target and its air defences. The missile follows a path semi-autonomously, on a low flight path guided by GPS and terrain mapping to the target area.[16] Close to the target, the missile climbs to increase its field of view and improve penetration, matches the target stored image with its IR camera and then dives into the target.[17][18]

Climbing to altitude is intended to achieve the best probability of target identification and penetration. During the final maneuver, the nose cone is jettisoned to allow a high resolution thermographic camera (infrared homing) to observe the target area. The missile then tries to locate its target based upon its targeting information (DSMAC). If it cannot, and there is a high risk of collateral damage, the missile is capable of flying to a crash point instead of risking inaccuracy.[17]

Enhancements reported in 2005 included the capability to relay target information just before impact and usage of one-way (link back) data link to relay battle damage assessment information back to the host aircraft, under development under a French DGA contract. At the time, inflight re-targeting capability using a two-way data link was planned.[19] In 2016, it was announced that Storm Shadow would be refurbished under the Selective Precision Effects At Range 4 (SPEAR 4) missile project.[20]

Some reports suggest a reduced capability version complying with Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) restrictions was created for export, for example to the United Arab Emirates.[21][22][23]

The missile relies on classified American-owned cartographic data, using Terrain Contour Matching or TERCON, to guide the missile to the target. This gives the American government veto of any sales to foreign countries under ITAR. In 2018 the French government tried to bypass this by creating a “ITAR-free” version of the missile for sale to Egypt that didn’t use TERCON. The missiles would have relied solely on GPS and inertial navigation systems to get to the target. Making the missile more vulnerable to Electronic Warfare. An issue in Ukraine where Russian jams GPS signals, so American approval is necessary for the missiles to operate to peak performance.[24] [25]

History

[edit]

Matra and British Aerospace were selected as the prime contractors for the Conventionally Armed Standoff Missile (CASOM) in July 1996; their Storm Shadow missile beat submissions from McDonnell Douglas, Texas Instruments/Short Brothers, Hughes/Smiths Industries, Daimler-Benz Aerospace/Bofors, GEC-Marconi and Rafael[26][27] The Storm Shadow design was based on Matra's Apache anti-runway cruise missile.[27] A development and production contract was signed in February 1997, by which time Matra and BAe had completed the merger of their missile businesses to form Matra BAe Dynamics.[28] France ordered 500 SCALP missiles in January 1998.[29]

The first successful fully guided firing of the Storm Shadow/SCALP EG took place at the CEL Biscarosse range in France at the end of December 2000[11] from a Mirage 2000N.

The first flight of Storm Shadow missiles on the Eurofighter Typhoon took place on 27 November 2013 at Decimomannu Air Base in Italy, and was performed by Alenia Aermacchi using instrumented production aircraft 2.[30]

The SCALP EG and Storm Shadow are identical except for how they integrate with the aircraft.[31]

In July 2016, the UK's MoD awarded a £28 million contract to support the Storm Shadow over the next five years.[32]

The missile was made ITAR-free at the initiative of France.[33]

Combat use

[edit]

RAF Tornados used Storm Shadow missiles operationally for the first time during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[34] Although they were yet to officially enter service, "an accelerated testing schedule" saw them employed by the RAF's 617 Squadron in the conflict.[35][36][37]

During the 2011 military intervention in Libya, the Storm Shadow/SCALP EG was fired at pro-Gaddafi targets by French Air Force Rafales[38][39] and Italian Air Force and Royal Air Force[40][41] Tornados. Targets included the Al Jufra Air Base,[42] and a military bunker in Sirte, the home town of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.[43] In December 2011, Italian defence officials noted that Italian Tornado IDS aircraft had fired between 20 and 30 Storm Shadows during the Libyan Campaign. This was the first time that Italian aircraft had fired the missile in live combat, and it was reported the missile had a 97 per cent success rate.[44]

French aircraft fired 12 SCALP missiles at ISIS targets in Syria as part of Operation Chammal. These launches took place on 15 December 2015 and 2 January 2016. It is thought that these firings may have been approved after a decision by the French MoD to reduce their inventory of SCALP missiles to reduce costs.[45] On Sunday 26 June 2016 the RAF used four Storm Shadow missiles against an ISIS bunker in Iraq. The Storm Shadow missiles were launched from two Tornado aircraft. All four missiles scored direct hits, penetrating deep into the bunker. Storm Shadow missiles were used due to the bunker's massive construction.

In October 2016 the UK Government confirmed UK-supplied missiles were used by Saudi Arabia in the conflict in Yemen.[46]

In April 2018 the UK Government announced they used Storm Shadow missiles deployed by Panavia Tornado GR4s to strike a chemical weapon facility in Syria.[47] According to US Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Kenneth Mckenzie, the Him Shinshar chemical weapons storage facility near Homs was hit by 9 US Tomahawks, 8 British Storm Shadows, 3 French MdCN cruise missiles, and 2 French SCALP cruise missiles.[48][49] Satellite images showed that the site was destroyed in the attack.[50] The Pentagon said that no missiles had been intercepted, and that the raids were “precise and overwhelming”.[51] In response, the Russian Ministry of Defence, during a press conference in Moscow, presented parts of what they claimed was a downed Storm Shadow missile.[52][53]

It has been suggested that Storm Shadows, deployed by either Emirati Mirages or Egyptian Rafales, could have been used in the July 2020 airstrike against Al-Watiya Air Base during the Second Libyan Civil War.[54] The attack against the base, which housed Turkish military personnel supporting the internationally recognized Government of National Accord, injured several Turkish soldiers, destroyed their MIM-23 Hawk anti-aircraft missiles systems and their KORAL Electronic Warfare System.[55][56][57][58]

On 11 March 2021, two Royal Air Force Typhoon FGR4 jets operating out of RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus hit a cave complex south west of the city of Erbil in northern Iraq, where a significant number of ISIS fighters were reported, marking the first combat use of the Storm Shadow from the Typhoon.[59][60]

Use by Ukraine

[edit]On 11 May 2023, the United Kingdom announced that it was supplying Storm Shadows to the Ukrainian military during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This followed a pledge from the UK in February 2023 to send Ukraine long-range missiles in response to Russian strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure. Ukraine has insisted it would not use such weapons on Russian territory. UK Defence Minister Ben Wallace emphasized the delivery as a "calibrated, proportionate response to Russia's escalation", noting Russian use of even longer-range munitions including the Kh-47M2 hypersonic missile, 3M-54 Kalibr cruise missile, and Shahed-136 one-way attack drone.[61][62]

The grant of Storm Shadow missiles is a significant boost to the Ukrainian military, as they are capable of striking targets at much longer ranges than had previously been possible, including command-and-control nodes and logistics points in occupied Crimea to interrupt Russia's ability to support the frontline.[63] Shortly after, France announced it would be delivering the SCALP EG, its version of the missile, to Ukraine as well. France said it was not delivering weapons capable of hitting Russian soil.[64] The UK on 18 May confirmed Ukraine had already successfully used the Storm Shadow.[65] Although no information was publicly disclosed regarding when exactly the French missiles were delivered to Ukraine, Ukraine's ambassador to France, Vadym Omelchenko, confirmed in an interview with LB.ua on 22 August 2023 that all SCALP missiles promised by French president Emmanuel Macron had been delivered already, likely by the time of the latter's announcement in May. Omelchenko further stated that the first batch of missiles (reported by some outlets to number 50 units) had more than proven its worth and that supplies of SCALP batches by France would continue.[66][67] Previously, on August 6, a few days after the attack on the Chongar Strait railway bridge, the SCALP's operational status in Ukraine had visually been confirmed as were its use in the attack and its successful integration to Ukrainian Su-24 bombers.[68]

Russia claimed Ukraine used Storm Shadow missiles to strike industrial sites in Luhansk on 13 May 2023, just two days after their delivery had been announced.[69] According to a report by Russian news outlet Izvestia, the cruise missiles are launched from specially modified Su-24 strike aircraft and fly under the cover of MiG-29 and Su-27 fighters equipped with AGM-88 HARMs. Ukrainian command also uses UAVs and ADM-160 MALD decoys to divert Russian air defenses and protect the aircraft and ordnance from being intercepted.[70] Ukraine's Minister of Defense Oleksii Reznikov confirmed the Su-24 as the Ukrainian Air Force's Storm Shadow launch platform, tweeting a photo of a Su-24MR with a missile on each of its inboard underwing pylons.[71][72] The pylons use an adaptor derived from retired RAF Tornado GR4 aircraft.[73]

Reznikov said at the end of May that the missiles had hit 100% of their targets,[74][75] although Russia's Defence Ministry has claimed to have shot some down.[76][77]

On 12 June, a strike which involved the Storm Shadow killed Major General Sergey Goryachev in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. At the time he was Chief of Staff of the 35th Combined Arms Army.[78] On 22 June, the Chonhar road bridge connecting Crimea with Kherson Oblast was struck by a Storm Shadow missile to interrupt Russian logistics.[79][80] A largely intact Storm Shadow crashed in Zaporizhzhia in early July. TASS claimed Russian forces had shot it down and recovered the wreckage to study the missile's design and help develop countermeasures to it.[81][82]

On 9 July 2023, Storm Shadow/SCALP missile was shot down by Russian air defence and captured later.[83]

On 29 July 2023, a Storm Shadow or SCALP missile hit the Chongar Strait railway bridge linking occupied Crimea with the Kherson Oblast, landing between the two tracks on the bridge approach.[84][85]

On 13 September 2023, Storm Shadow and/or SCALP missiles were used in a strike against the Sevastopol port,[86][87][88] seriously damaging the Rostov na Donu submarine and seriously damaging (according to some sources, beyond repair[89]) the Ropucha-class landing ship Minsk.[90][91][92]

On 22 September 2023, at least three Storm Shadow and/or SCALP missiles hit the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in Sevastopol.[93][94][95] According to the Ukraine military, the missile attack targeted a meeting of the Russian Navy's leadership. "After the hit of the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, 34 officers were killed, including the commander of the Russian Black Sea Fleet", they said. While no confirmation of Sokolov's alleged death is known, neither has any reliable source depicted him as alive and well since the attack took place. They also claimed that the strike wounded at least 100 other Russian service personnel.[96]

On 26 December 2023 it is believed two Storm Shadow and/or SCALP missiles were launched against the Russian occupied port of Feodosia with the Russian landing ship Novocherkassk being hit and turned into a burning wreck.[97][98][99]

At a news conference on 28 May 2024, French President Macron said he permitted Ukraine to use SCALP missiles to strike targets inside Russia, a major departure from previous guidelines that restricted the use of foreign-supplied weapons only to occupied territory. This expansion of use is still restricted to neutralization of military facilities being used for attacks into Ukraine.[100]

In July 2024, the British Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced that the British government would allow the defensive use of Storm Shadow missiles on targets inside Russia.[101]

On 25 September 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin warned the West that if attacked with conventional weapons Russia would consider a nuclear retaliation,[102] in an apparent deviation from the no first use doctrine.[103] Putin went on to threaten nuclear powers that if they supported another country's attack on Russia, then they would be considered participants in such an aggression.[104][105] Experts say Putin's announcement is aimed at dissuading the United States, the United Kingdom and France from allowing Ukraine to use Western-supplied long-range missiles such as the ATACMS and Storm Shadow in strikes against Russia.[106]

Export variant

[edit]Black Shaheen

[edit]Developed by France for export to the United Arab Emirates for use with its Mirage 2000, modifications were made to reduce the range reportedly to 290 km (160 nmi; 180 mi) in order to comply with Missile Technology Control Regime guidelines.[31]

MdCN

[edit]In 2006, MBDA France[107] began the development of a more potent deep strike naval cruise missile to be deployed on a new series of French warships and submarines for land-attack operations in order to complement the SCALP/Storm Shadow. This Missile de Croisière Naval (MdCN),[108] formerly dubbed SCALP Naval, became operational on the French FREMM multipurpose frigates in 2017[109][110] and on Barracuda-class submarines in June 2022,[111] using the A70 version of the Sylver launcher on the former[112] and the 533 mm torpedo tubes on the latter.[113] As it is not launched from a plane like the SCALP, the MdCN uses a booster during its launch phase to break out of the ship and gain some initial velocity.[114]

Despite the fact that it was previously called SCALP Naval, it is not a variant of the Storm Shadow, has no stealth shaping, but is a more conventional, longer range sea-launched cruise missiles very similar to Tomahawk.

Replacement

[edit]Between 2016 and 2018, France and the United Kingdom began jointly developing a replacement for Storm Shadow/SCALP for both the French Air and Space Force and the Royal Air Force, as well as the Exocet and Harpoon anti-ship missiles for the French Navy and Royal Navy. As of 2022, the program was examining two complementary concepts; a subsonic, low observable missile and a supersonic, highly manoeuvrable missile.[115] On June 20th 2023 at the Paris Air Show, Italy signed a letter of intent to join the program.[116] Italy confirmed its initial funding contribution in November and this also came with the announcement that the program would produce a deep-strike land-attack missile by 2028 and an anti-ship missile by 2034.[117]

Operators

[edit]

Egypt

Egypt- 100+ delivered for the Egyptian Air Force as part of the Dassault Rafale deal.[118][119][120][121][122]

France

France- 500 SCALP missiles ordered for the French Air and Space Force in 1998. 50 MdCNs ordered in 2006 and a further 150 ordered in 2009 for the French Navy.[123]

Greece

Greece- 90 ordered for the Hellenic Air Force in 2000 and 2003.[124][125] More ordered and delivered in 2022 as part of the Dassault Rafale F3R deal.[126]

Italy

Italy- 200 ordered for the Aeronautica Militare in 1999.[22]

India

India- Unknown number ordered for the Indian Air Force in 2016 as part of the Dassault Rafale deal.[127]

Qatar

Qatar- 140 ordered for the Qatar Air Force in 2015.[128]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia- Unknown number ordered for the Royal Saudi Air Force.[31][129]

Ukraine

Ukraine- Unknown number donated by France, Italy, and the UK.

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates- Unknown number ordered for the United Arab Emirates Air Force in 1997. Known as Black Shaheen.[130][31][131]

United Kingdom

United Kingdom- The Independent estimated the order for the Royal Air Force to be between 700 and 1,000.[132]

See also

[edit]- 3M14A – (Russia)

- AGM-129 ACM – (United States)

- AGM-158 JASSM – (United States)

- BrahMos-A – (Russia, India)

- Delilah – (Israel)

- HN-1 – (China)

- HOPE/HOSBO – (Germany)

- Joint Strike Missile – (Norway)

- KD-88 – (China)

- Kh-55 – (Soviet Union)

- Kh-61/P-800 – (Russia)

- MTC-300 – (Brazil)

- Popeye – (Israel)

- Ra'ad-II – (Pakistan)

- Saber – (United Arab Emirates)

- SOM (missile) – (Turkey)

- Taurus KEPD 350 – (Sweden, Germany)

- Wan Chien – (Taiwan)

- YJ-12 – (China)

References

[edit]- ^ Sabbagh, Dan (2023-05-09). "British-led coalition hopes to supply longer-range missiles to Ukraine". the Guardian. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- ^ Janes (19 May 2023), "Scalp/Storm Shadow", Janes Weapons: Air Launched, Coulsdon, Surrey: Jane's Group UK Limited., retrieved 21 May 2023

- ^ Sheridan, Danielle; Nicholls, Dominic; Holl-Allen, Genevieve (11 May 2023). "Britain is first nation to send long-range missiles to Ukraine". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Kilner, James (13 May 2023). "'Nightmare' for Russia as Ukraine strikes base with British Storm Shadow missiles". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "The U.K. Has Given Ukraine the Storm Shadow: A Western Missile on a Soviet Warbird". Popular Mechanics. 2023-05-11. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "Apache (Anti-Runway Cruise Missile)". Armed Forces Europe. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Nouveau succès pour le missile de croisière naval" (PDF) (Press release). Direction générale de l'armement (DGA) (France). 4 July 2013.

- ^ "MOD signs £146 million contract to upgrade RAF's long-range missile". UK Government – Defence and armed forces. 22 February 2017.

- ^ "MBDA se voit confier la rénovation à mi-vie du SCALP". Air & Cosmos. 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Storm Shadow". RAF. 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03.

- ^ a b "Storm Shadow". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2004-06-03.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (May 24, 2023). "Su-24 Fencer Is Ukraine's Storm Shadow Missile Carrier". The Drive.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig (28 November 2013). "Eurofighter flies with Storm Shadow missiles". Flight Global. Reed Business Information. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Sweetman, Bill (14 January 2009), Eurofighter Typhoon Gains Altitude, Aviation Week, retrieved 20 March 2011[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Storm Shadow dropped from UK's F-35B follow-on integration plan". Jane's. Archived from the original on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ Handy, Brian (August 2003). "Royal Air Force Aircraft & Weapons" (PDF). DCC (RAF) Publications. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ a b Eklund, Dylan (2006). "Fire and Brimstone: The RAF's 21st Century Missiles". RAF Magazine. pp. 19–25.

- ^ "Technical Overview of the Storm Shadow Cruise Missile for Ukraine". designnews.com. 2023-05-12. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ "Storm Shadow/SCALP EG Cruise Missile". Defense update. 27 January 2005. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Defence Suppliers Service" (PDF). UK Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "USA angry over French decision to export Apache, Headlines". Jane's Defence Weekly. IHS. 8 April 1998. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ a b "APACHE AP/ SCALP EG/ Storm Shadow/ SCALP Naval/ Black Shaheen". Missile Threat. Center for Strategic and International Studies. 2 December 2016 [Modified 28 July 2021].

- ^ "Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)" (PDF). The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Clément Charpentreau (19 November 2024). "UK, France maintain fog of war on Storm Shadow missile use for strikes in Russia". aerotime. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ Pierre Tran (19 November 2024). "A jet sale to Egypt is being blocked by a US regulation, and France is over it". defensenews. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ Morrocco, John D. (29 July 1996). "BAe, GEC Snare Key U.K. Contracts". Aviation Week and Space Technology. McGraw-Hill, Inc. p. 64.

- ^ a b Evans, Michael (26 June 1996). "£4bn orders will equip RAF for the 21st century". The Times. Times Newspapers Ltd.

- ^ "£700 Million RAF Contract Signed". The Press Association Limited. 11 February 1997.

- ^ "France Takes Scalp". Flight International. Reed Business Publishing. 14 January 1998.

- ^ "Eurofighter flies with Storm Shadow missiles". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ a b c d "APACHE AP/ SCALP EG/ Storm Shadow/ SCALP Naval/ Black Shaheen". Missile Threat. Center for Strategic and International Studies. 28 July 2021 [2 December 2016]. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "New contract to support the RAF's long range missiles". UK Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ^ "Exportations : Comment MBDA desserre le nœud coulant des Etats-Unis (ITAR)". 27 March 2019.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: How RAF's Tornados made storming contribution". Flight International. 8 March 2019.

By then upgraded to the GR4 standard, the UK's ground-attack aircraft played a part in the opening salvoes of the second conflict with Saddam Hussein's forces in Iraq. This was a spectacular debut for its Storm Shadow weapons, which allowed pinpoint strikes to be conducted against key infrastructure targets from a launch distance of more than 135nm (250km).

- ^ "617 Squadron". Raf.mod.uk. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

2003 – Flew the RAF's first operational mission using Storm Shadow.

- ^ Almond, Peter; Carr-Brown, Jonathon (30 March 2003). "Dambusters test-fire new missile". Sunday Times. London.

[Wing Commander Robertson] set about completing his mission – firing Britain's first air-launched cruise missile, the Storm Shadow.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig (6 July 2004). "Flying colours; Last year's Iraq conflict was a solid test for the UK RAF after a decade that has brought it closer to industry. Its highest ranking officer discusses its performance". Flight International.

- ^ "Rafale destroys Libyan jet, as France steps up action". Flightglobal.com. 2011-03-25. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ^ "Libya: France May Shift Rafales from Rafaletown to Sigonella". Aviationweek.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-17. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ^ "British Armed Forces launch strike against Libyan air defence systems". Ministry of Defence. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "U.K. Libya Strikes Include Storm Shadows". Aviation week. 2011-03-20. Retrieved 2011-03-22.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Libye : premier tir opérationnel d'un missile de croisière Scalp par la France". Marianne2.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ^ "UK jets bomb Gaddafi hometown bunker". BBC News. 26 August 2011.

- ^ "Italy Gives Bombing Stats for Libya Campaign". Archived from the original on July 27, 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Tran, Pierre (7 January 2016). "Engine Support Surges With Rafale Flight Hours, Exports". Defense News. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ UK-Supplied Precision Weapons Prove Popular in Saudi-Led Yemen Campaign, Defensenews.com, 17 October 2016

- ^ "RAF jets strike chemical weapon facility in Syria". UK Government. Ministry of Defence and Gavin Williamson. 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Trump hails 'perfect' Syria strikes". Bbc.co.uk. 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Coalition launched 105 weapons against Syria, with none intercepted, DoD says". Militarytimes.com. 14 April 2018.

- ^ Gathright, Jenny (14 April 2018). "PHOTOS: 2 Syrian Chemical Weapons Sites Before And After Missile Strikes". Npr.org. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Ewen MacAskill, and Julian Borger (14 April 2018). "Allies dispute Russian and Syrian claims of shot down missiles". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Tomahawk и авиаракета доставлены из Сирии в Москву для изучения" [Tomahawk and air missile delivered from Syria to Moscow for study]. Тass.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Российские военные показали обломки выпущенных по Сирии крылатых ракет" [The Russian military showed the wreckage of cruise missiles fired at Syria]. Interfax.ru (in Russian). 25 April 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "UAE Dispatches Fighter Jets to Support Its Allies Against Turkey". Forbes.

- ^ "Turkish Forces Lick Wounds After Airstrikes Hit Their Base In Libya". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 8 July 2021.

- ^ "LNA destroys Turkish air defense, electronic warfare systems western Libya". Egypt Today. 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Airstrikes hit Libya base held by Turkey-backed forces". The Washington Post. 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Libya: Turkey vows 'retribution' for attack on its positions at al-Watiya airbase". Middle East Eye. 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Typhoon fires Storm Shadow operationally for first time". Janes.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Newdick, Thomas (15 March 2021). "British Typhoons Have Used Storm Shadow Cruise Missiles For The First Time In Combat". Thedrive.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Gregory, James (11 May 2023). "UK confirms supply of Storm Shadow long-range missiles in Ukraine". BBC News.

- ^ Ukraine gets British long-range missiles ahead of counteroffensive. Defense News. 11 May 2023.

- ^ Armed with Storm Shadow, Ukraine could ‘starve’ Russian front lines of logistics, leadership. Breaking Defense. 16 May 2023.

- ^ Altman, Howard (May 16, 2023). "Ukraine Situation Report: France Sending SCALP-EG Cruise Missiles". The Drive.

- ^ Ukraine has ‘successfully’ used UK-provided Storm Shadow missiles against Russia, British Defense Secretary tells CNN. CNN. 18 May 2023.

- ^ Ambassador: France has handed over all promised in the first batch SCALP missiles to Ukraine. MILITARNYI. 22 August 2023.

- ^ Ukrainian ambassador in France announces further batches of long-range SCALP missiles. Ukrainska Pravda. 22 August 2023.

- ^ French SCALP-EG Cruise Missiles Officially In Use In Ukraine. The Drive. 6 August 2023.

- ^ Russia says Ukraine used Storm Shadow missiles from Britain to attack Luhansk. Reuters. 13 May 2023.

- ^ Ukraine's ‘Specially Modified’ Warplane Under Cover Of MiG-29 & Su-27 Pounds Russia With Storm Shadow Missiles; UK Confirms Its Use. The EurAsian Times. 19 May 2023.

- ^ Su-24 Fencer Is Ukraine's Storm Shadow Missile Carrier. The Drive. 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine conflict: Ukraine employing Su-24 to carry Storm Shadow, defence minister reveals". Janes Information Services. 25 May 2023. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023.

- ^ "Retired Tornado parts used to launch Ukrainian Storm Shadows". UK Defence Journal. 2 July 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Storm Shadow missiles show 100% efficiency in Ukraine – Ukraine's Defence Minister". Yahoo! News. May 29, 2023.

- ^ Ukraine says Storm Shadow missiles have hit '100%' of intended Russian targets. Forces.net. 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Russian forces intercept two British Storm Shadow missiles, defence ministry says". Reuters. 2023-05-27. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ Ukraine's defense ministry says its Storm Shadow long-range missiles have hit 100% of their targets. Business Insider. 28 May 2023.

- ^ Allison Quinn (13 June 2023). "Russians Mourn 'Best' General as Ukraine Counteroffensive Gains Ground". Yahoo! News.

- ^ "Zelensky says Russia is planning to sabotage Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant". Washington Post.

- ^ Ukraine Strikes Key Bridge To Crimea, Hints At More Long-Range Attacks. The Drive/The War Zone. 22 June 2023.

- ^ Crashed Storm Shadow Missile Falls Into Russian Hands. The Drive/The War Zone. 5 July 2023.

- ^ Russia says it's snagged the intact parts of a Storm Shadow missile, and can now study the British-made munition that's been devastating its operations in Ukraine from long range. Business Insider. 7 July 2023.

- ^ Newsroom (2023-07-09). "Russian troops seize near intact UK Storm Shadow missile". Modern Diplomacy. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ French SCALP-EG Cruise Missiles Officially In Use In Ukraine. The Drive. 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine Situation Report: Key Crimean Railway Bridge Targeted In Missile Strike". 31 July 2023.

- ^ Ukraine says bomber deployed British and French cruise missiles 'perfectly' in major attack on Russian navy. Sky News. 15 September 2023.

- ^ Russian Submarine Shows Massive Damage After Ukrainian Strike. The Drive. 18 September 2023.

- ^ "British cruise missiles were used in significant Ukrainian attack on Russian submarine". Sky News. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Oryx. "Attack On Europe: Documenting Russian Equipment Losses During The Russian Invasion Of Ukraine". Oryx. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ "Two Russian Navy Black sea ships hit by missiles, one destroyed VIDEO". 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine launches missile attack on Crimea". BBC News. 2023-09-13. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Edwards, Tim (2023-09-13). "Ukrainian missiles strike Russian warships in Crimean naval base". CNN. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Black Sea Fleet Headquarters Takes Direct Hit From Cruise Missile. The Drive. 22 September 2023.

- ^ Ukraine hits HQ of Russia's symbolic Black Sea navy. BBC. 22 September 2023.

- ^ Barnes, Joe (22 September 2023). "Storm Shadow missile 'tears open' Black Sea Fleet HQ in Crimea". Telegraph. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ Picheta, Rob (2023-09-25). "Ukraine claims commander of Russia's Black Sea Fleet was killed in Sevastopol attack". CNN. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ Frappe ukrainienne en mer Noire: «La marine russe est désormais sur la défensive». RFI. 27 December 2023.

- ^ La marine russe a perdu un bâtiment de débarquement de chars en mer Noire. Mer et Marine. 27 December 2023.

- ^ Kilner, James (26 December 2023). "Watch: Russian warship sunk in suspected Storm Shadow missile attack". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Macron Allows Ukraine to Use French Missiles to Strike Inside Russia". Wall Street Journal. 28 May 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Keir Starmer gives go-ahead for British missiles to be used in strikes against targets inside Russia". Sky News. Retrieved 2024-07-11.

- ^ "The Unthinkable: What Nuclear War In Europe Would Look Like". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 27 September 2024.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (2024-09-25). "Vladimir Putin warns west he will consider using nuclear weapons". The Guardian. Retrieved 2024-09-26.

- ^ "Putin's nuclear red line: Does he actually mean it?". Euractiv. 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Putin's nuclear threats: empty rhetoric or a shift in battlefield strategy?". France 24. 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Putin lowers bar for nuclear strike amid Ukraine attacks: Why it matters". Al Jazeera. 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Communiqué de presse" (PDF). 4 July 2013.

- ^ French frigates getting cruise missiles – UPI.com, 7 June 2017

- ^ "Final Qualification Firing for French Naval Cruise Missile". Sea Technology. 1 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ "French Navy Fitting Aster 30 Long Range SAM on its Last Two ASW FREMM Frigates". Navyrecognition.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Vavasseur, Xavier (21 October 2021). "World's Newest Class of Nuclear Attack Submarine: Rare Access Inside Suffren". Navalnews.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Premier tir réussi pour le missile de croisière Scalp Naval" (in French). Mer et Marine. 16 June 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "UK and France advance future cruise / anti-ship weapon project | Press Release". MBDA. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ Vavasseur, Xavier (2023-06-26). "Italy Joins France and the UK for FC/ASW Program". Naval News. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ "Italy finally funds naval missile projects | Shephard". www.shephardmedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-20.

- ^ "Missili a lungo raggio venduti e consegnati all'Egitto di al-Sisi dal consorzio europeo Mbda (al 25% dell'italiana Leonardo)". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Egyptian Air Force displays SCALP cruise missile". 3 Feb 2021. Retrieved 11 Feb 2021.

- ^ "Photos: Egypt's army reveals SCALP stealth missiles". Egyptindependent.com. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Egyptian Air Force displays SCALP cruise missile". Janes.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Scalp EG/Storm Shadow/Black Shaheen". Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Projet de loi de finances pour 2013 : Défense : équipement des forces" (in French). Senate of France. 22 November 2012. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ "SCALP-EG". Hellenic Air Force. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Η πολεμική αεροπορία διαθέτει πύραυλο κρουζ". Newsbeast.gr. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "All Greek Rafales will be at the latest F3R standard". Meta-Defense. 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Shukla, Tarun (23 September 2016). "India signs $8.9 billion Rafale fighter jet deal with France". Livemint.

- ^ "Qatar Emiri Air Force To Get The Full Range of MBDA Missiles for its 24 Rafale fighters 0705152". Airrecognition.com. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Storm Shadow Sale Confirmed". Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ "MBDA to Supply MICA and SCALP EG / STORM SHADOW Missile Systems to the Hellenic Air Force". Defense-aerospace.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Storm Shadow / SCALP Long-Range, Air-Launched, Stand-Off Attack Missile". Airforce Technology. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Bellamy, Christopher; Brown, Colin (25 June 1996). "Thousands of jobs shielded by new military spending". The Independent. London.

External links

[edit]- Cruise missiles of the United Kingdom

- Cruise missiles of France

- Naval cruise missiles

- Military equipment introduced in the 2000s

- Post–Cold War missiles of the United Kingdom

- Cruise missiles

- Air-launched cruise missiles

- Military equipment of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Stealth cruise missiles

- MBDA

- Surface-to-surface missiles of the United Kingdom

- Surface-to-surface missiles of France